[#5] Can Indian companies (like Flipkart and Zomato) shape-shift into innovation platforms?

While most asian upstarts are attempting this, who stands to win?

Welcome to another edition of Bizit, by Pratyush and Aditya. It’s taken us quite a lot of work to get this up and running and we’re very grateful for the initial support we’ve got from all of you.

You can head over to the Archives to read all the content we’ve published in the past couple of days.

Starting Up? Think platforms and not products

Many venture capitalists will tell you that today they would rather invest in a platform as opposed to a standalone product. This may strike you as a surprisingly hedged bet for the ever so risky VC business, but it is because of the proven potential of the platform companies.

Some time ago, I talked about how Microsoft established itself as a platform in a LinkedIn post. Bill Gates’ decision to give away the basic software to IBM’s mainframe computers for free is the most striking and early example of the potential platforms carry.

Many would call him lucky but it was Gates’ genius which realized there would be more than “one side” to the market around IBM-compatible PCs. The aim of the deal wasn’t to maximize profits from MS-DOS (Disk Operating System) as a standalone product. Instead, the strategy was to turn DOS into an industry-wide platform that others would use as a foundation to build compatible software applications for the PC market thereby making the DOS indispensable.

Microsoft was thinking platforms while IBM was thinking products.

Source

Despite acquiring the cult status, not many people pause to break down how exactly platforms work and what real potential they have. I wish to address this whitespace by not only sharing my perspective but also leaving behind the tools and frameworks you'll need to form your own.

WTF is a Platform?

We’ve covered platforms in an earlier edition.

In a platform, unlike other traditional businesses, success doesn’t depend on the quality, price, or timing of the entry of a standalone product. Rather the success depends on the complementary innovations that defined what users could do with the product. In fact, these complements added the essential value to the core product.

If I were to write an executive summary — platforms, in general, connect different individuals and organizations for a common purpose or to share a common resource. It is often synonymous with an “ecosystem” where they bring individuals and organizations together so that they can innovate or interact in ways not otherwise possible and hence their value can (potentially) increase non-linearly.

Source

But first things first, if you’re reading this newsletter for the first time, please take a moment and consider signing up.

But when/why do we build a Platform?

I am no expert but a platform strategy seems to work better when —

It is more “economical” to enable transactions instead of owning the assets and delivering products/services directly — think the Gig economy companies like Uber and Airbnb.

It makes more sense to tap the innovation capabilities of outside firms to enhance value and scale — think Operating Systems like Windows and Android.

In a platform market, the better platform almost always trumps the better product. For instance, the Apple Macintosh was always “the” better personal computer than Windows PCs in terms of design, elegance, and ease of use (I would argue the same holds true even today as I am typing this on a MacBook Air). Despite the obvious strengths, its market share was abysmal (around single digits) because it was too difficult to build applications for and the higher prices didn’t encourage mass adoption.

Another astonishing example would be that of Google Cloud, which despite boasting of superior technology, engineers, products, and services, simply hasn’t been able to take off.

What are the types of platforms?

Essentially, platforms are of two types and as long as we remember the executive summary definition, we would be able to effectively understand both of them, just fine.

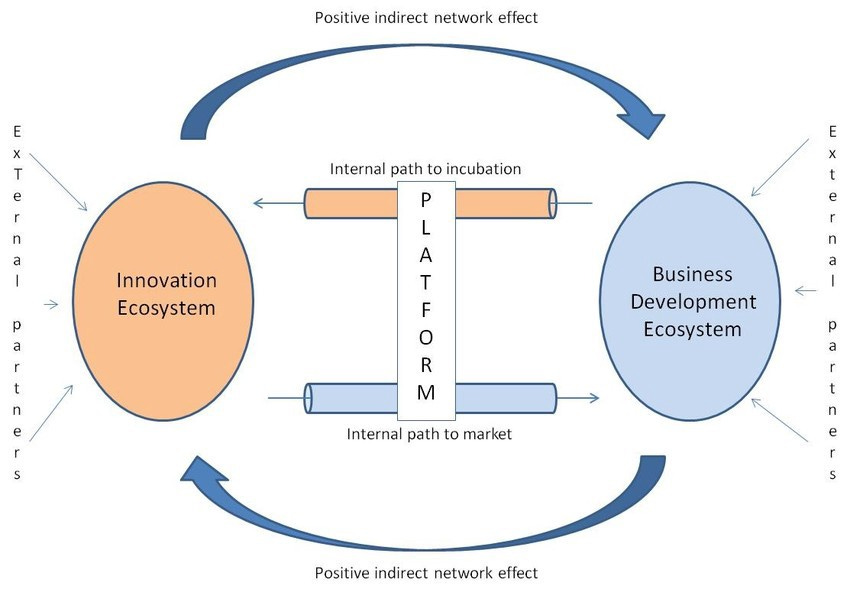

The first type is an innovation platform. Such platforms usually consist of common (technological) building blocks which the owner and the participants/partners of the ecosystem share and create new complementary products on top. These products add functionality or provide access to assets that make the platform indispensable. Popular examples include Google Android, Microsoft Windows, Amazon Web Services, etc.

The second type of platform is popularly called transaction platforms, which are largely intermediaries, like online marketplaces, that facilitate exchange (or transaction) of information, goods, and services. The more transactions on the platform, the more valuable it becomes. In the digital world, popular transaction platforms are Google Search, Facebook, and Amazon Marketplace. Some recent, but popular, examples would include Airbnb and Uber. Local names like Flipkart and Zomato are also transaction platforms.

Interestingly, companies like Visa and Mastercard were the pioneers of digital transaction platforms but originated quite before the digital era but don’t get a lot of credit.

It’s easy to get lost amidst the striking similarities between the two types of platforms as both of them have a central theme — shared resources. But there are important strategic differences between the two platform types.

Innovation platforms tend to enable the creation of complementary products and services, built mostly by 3rd party firms but without supplier contracts. They monetize it by charging the 3rd parties for development fees and by directly selling/renting the product. By contrast, transaction platforms create value by facilitating the exchange of goods/services/information and monetize it by collecting transaction fees (Visa/Mastercard), charging for advertising (Facebook/Google Search), or both (Google Android/Amazon Marketplace).

Often, the most successful and valuable firms start with one type of platform and venture into the other by either adding/linking/mixing the two and following a hybrid strategy. And this is what we will be discussing next.

India and Bharat: 2 different names, 2 different games

India in 2019, is developing so fast that terms like traditional, conventional, obsolete and futuristic change meanings every other year. Peculiarly, when it comes to technology, India leapfrogs the technology evolution stage. Conventional internet for the world was desktop but we skipped desktop and the internet was mobile-first for us. We also skipped 3G and went straight to 4G.

Because the current crop of internet users (~200 million) shared a lot of common behavioral aspects (like understanding the internet or how to use a smartphone), customer acquisition strategy was more about solving the trust issue. Hence, Flipkart was born by creating a replica of the famed Amazon Marketplace model with the exception of one innovation — Cash on Delivery (CoD).

At inception, the battle was about winning the user’s trust but it proliferated through the entire value chain. The delivery boy was now a mini-bank because most of the early adopters chose CoD as the method of payment. There were also a lot of return orders through the app under the 30-day return guarantee which was the cause of distrust of sellers on the platform. Disloyal customers were rewarded more than loyal customers through cashback.

And hence, the set of skills required to acquire this avalanche of customers was very different. The conventions of the western world didn’t quite apply.

India (Bharat) is changing again, and the next 500 million internet users will be vernacular speaking. I would like to think that they may entirely skip the traditional graphical interface and go straight to Voice. This means what was traditional in 2009 is now obsolete, and what was futuristic in 2015 will soon be the new conventional.

Bharat is no longer in connection-infancy and has a critical mass of people who use their phone for a lot more things than just making phone calls. Solving for Bharat requires an in-depth understanding of the issues surrounding the users.

Connecting Bharat

“If you talk to a man in his language, it goes to his heart” — Nelson Mandela.

The first wave of consumer internet companies in India was built for English speaking users. English language content accounted for 56% of the content on the internet, while Indian languages accounted for less than 0.1%.

Thanks to the Jio revolution, mobile internet usage in India has seen unprecedented growth. Bharat would add half a billion users to its smartphone user base, and these users would be local language users.

But this is no longer the case, and clearly, Bharat loves vernacular content as shown by the success of Dailyhunt/Newshunt. Other brands followed suit and understood that quickly adapting to the needs of their customers is the only way to stay relevant and ubiquitous. Amazon India, in its ambitious pursuit of serving every zip code in the country, was among the first non-Indian company to launch a Hindi website in an attempt to lower the barriers for their customers.

However, lowering the barriers isn’t the same as understanding the problems plaguing the users. The Bharat users aren’t comfortable with English, don’t understand icons such as the magnifying glass for search, and don’t feel comfortable clicking on URLs or tapping on their keyboards. They prefer consuming visual or voice and vernacular, and that is fundamentally the approach that the more successful new media startups like Sharechat and TikTok have adopted.

Play, Pause, and Order (PPO): The new customer trend?

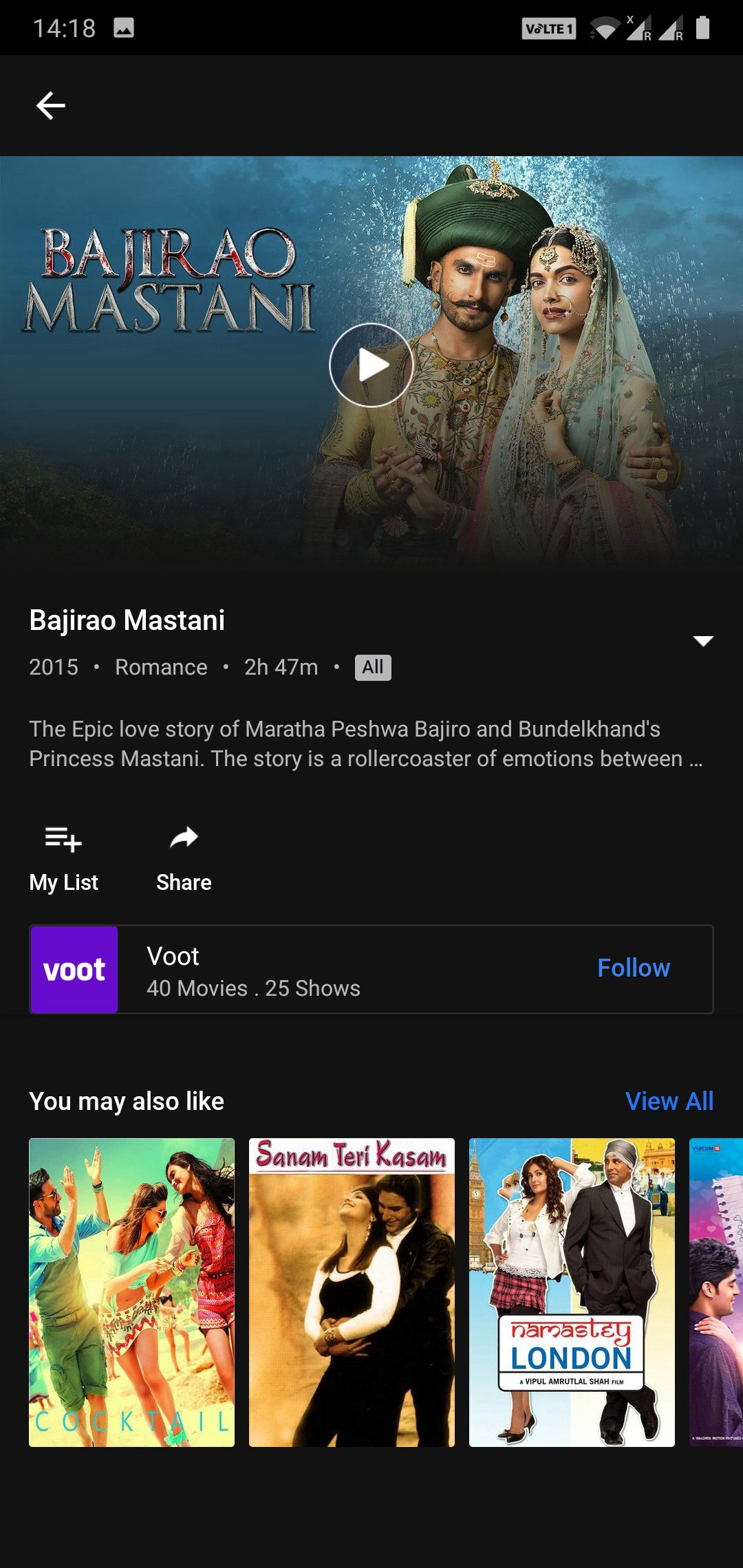

Last year, Flipkart launched its streaming service with a bid to increase customer loyalty and prevent app uninstalls, especially among the tier 2/3 cities. The strategy seems to have worked with Flipkart’s share in the recently concluded festive season standing north of 60% in terms of GMV. I tried connecting the dots here.

This approach was soon followed by Zomato, which plans to reel in more customers with video content. On average, a Zomato customer logs into the app once a week to order food. With 3-to-15 minute Over-the-top (OTT) originals catalog comprising of shows, recipes, and restaurant stories, it expects its customers to spend more time on the app and correspondingly place more orders.

Indians clearly love video-content and brands are not shy of investing in it especially when the next avalanche of internet users in the country would come from Bharat. However, executing the PPO strategy (if you are a college student and reading this — it is not what you think) is tricky as brands are always at the risk of plunging into competition with platforms that have deeper pockets, greater expertise and hence the quality of content is much better.

Great Minds Think … A̶d̶s̶ Attention

“The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads.” — The quote by early Facebook employee Jeff Hammerbacher is an embarrassing relic that is often confused. People tend to get swayed by these notions and miss things written in the fine print. The essence of the quote isn’t digital advertising; instead, it is about retaining the attention span of the users.

For instance, more than half of Facebook’s 2.4 billion Monthly Active Users (MAUs) log into the platform daily and spend 58 minutes on an average. In the process, 300 million photos are uploaded and 8 billion videos are watched daily.

Compare this with Google’s cash cow, YouTube, which has 1.5 billion MAUs but only 30 million out of them use it on a daily basis. However, it’s interesting to note that the average visit length for a user is 40 minutes.

Armed with this stickiness Facebook has morphed itself as an innovation platform starting as a transaction platform.

Facebook started as a transaction platform allowing the exchange of messages between one side of the users. Remember — this was the time when you used to recharge your mobile with SMS packs to chat with your friends and thus this concept was a game-changer. However, it was only when this side of the users was very, very large, Facebook started onboarding advertisers, application developers, and digital content partners. This was their pivot towards becoming an innovation platform.

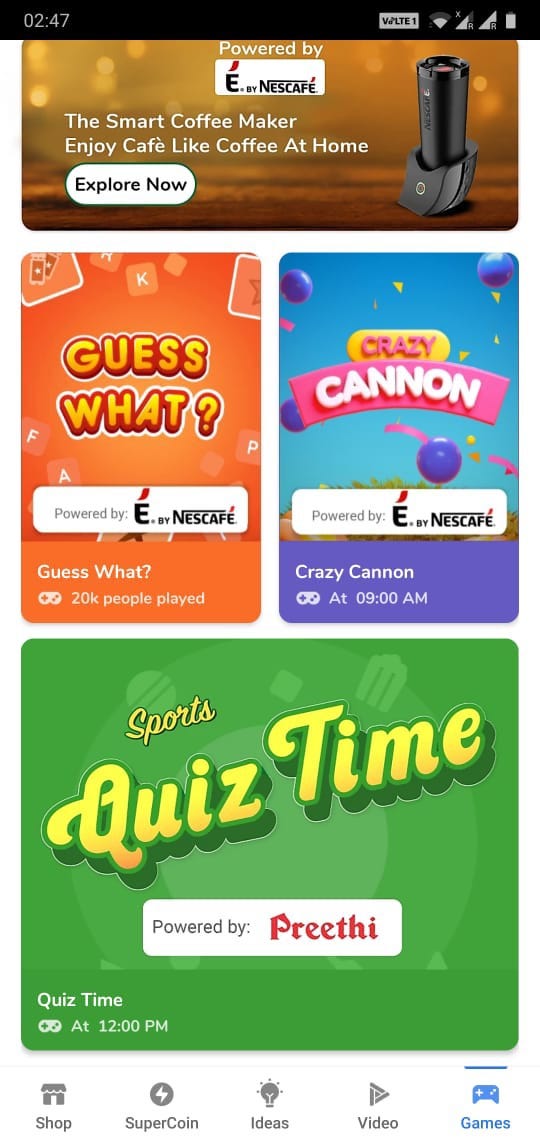

It seems as if Flipkart is sending its senior management back to school to learn about this case study. With its losses getting absorbed into the sizeable top line of Walmart, there couldn’t have been a better time. Between launching videos and the time of writing this, Flipkart is aggressively betting on games too.

It isn’t alone in this pursuit, though. The food-tech company, Zomato, with the zeal of its founder to make dining outside accessible, has been ruthlessly executing and catching up fast. Unlike Flipkart, Zomato deals with perishable goods and faster transactions. This ensures that users are likely to visit the app more frequently. This coupled with their 70 million Monthly Active Users (MAUs) puts Zomato in the contention for becoming an innovation platform.

What next?

Back on their core strengths of facilitating transactions, I expect a lot of transaction platforms adopting this path towards rapid user growth and retention. I also know that this is going to grow, get copied, and start popping up everywhere and the market will likely be a “Winner take all/most” as everyone is competing for the same 3–4 hours an average Bharat user would spend on his/her smartphones daily.

As a content platform scales, deep ecosystem partnerships with handset makers, content creators help create a strong moat over any potential competition. Hence, expect someone like a Flipkart/Paytm giving away smartphones with pre-installed app bundles to customers and recovering the device cost through payment installments. Of course, profitability will require a lot of math but they have some super-smart folks crunching numbers for them and I am sure that they’ll figure a way out.

The only challenge, however, is that most of the transaction platforms are burning cash in their quest to acquire users fast and at all costs. And this “Big Boy strategy for a Big Boy game” is only going to add more gasoline to the cash burn.

Will the existing investors wait with bated breath as the founders unfurl one version of their story after the other justifying their aggressive approach and their lofty valuations or will they lose patience and start demanding returns as usually if something looks like a duck and walks like a duck and feels like a duck, it is a duck.

With the substantial localized know-how and scale of these transaction platforms, expect the trend to catch on and a few but big winners.

We’d love to know why you agree/disagree. Let us know what you think in the comments.

We’ve covered the following -

We’re constantly listening for suggestions and feedback to improve.

So, it’d be great if you let us know how you like our newsletter so far.

In case we haven’t met, I’m Pratyush Choudhury.

Thank you for reading. We hope it was worth the while and left you better than it found you! :)

——

And if you enjoyed reading this article, please share further.