[#7] Platforms Part - 2: The Economics

An economics lens to understand why platform companies behave the way they behave

In many previous articles on our newsletter, Pratyush wrote about how platform businesses today are evolving into a hybrid transaction & innovation model.

Today I am going to pen down some thoughts I had about the economics of platforms for a long time, and I have come to realize that platforms are indeed exceptional. In this piece, I have done an in-depth analysis using some microeconomics and have tried to draw insights based on that.

Before we move on, if you’re reading this newsletter for the first time, please take a moment and consider signing up.

What are platform businesses?

I am using the term very generally, but essentially platform businesses are those which create value by facilitating an exchange between one or more "sides".

The article is aimed to help people apply concepts of economics to reach conclusions about how platform businesses will shape up. For the same, let’s start with the following assumptions about platforms. Later in the article, when we discuss various cases, we can see how changing these assumptions modify the outcome.

For now, I am contending that platforms have the following three properties:

Natural Monopolies (Powerful & unlimited economies of scale)

Network effects

Difficult to differentiate

While the last two may be simple enough to understand, let's take a little detour here for a bit for understanding what I mean by "natural monopolies".

A crash course in microeconomics

In any market, we have a demand curve and a supply curve, as shown below. The demand curve denotes how many units of the product the market is willing to buy at that price, and it's reasonably intuitive. Demand falls as the price rises & vice versa. The supply curve denotes the number of units a supplier is willing to sell at the given price.

The point at which they meet is the efficient price outcome at which Demand = Supply & the market clears.

The supply curve is not as intuitive and takes some explanation. Before we go into that, let’s define marginal cost. Marginal cost is the cost incurred by the company to sell one extra unit in the market.

The supply curve is actually the same as the marginal cost curve of all the suppliers in the market.

Think about it. As a supplier, I would stop supplying as soon as the cost of one additional product becomes higher than the price offered in the market. But I will keep providing until then.

That begs the question, "If the supply curve is just the marginal cost curve of firms, then why is the cost of an additional unit increasing? What happened to economies of scale?"

Well, economies of scale do exist. The marginal cost curve is actually U-shaped.

Why did it start increasing? Think about a factory with capacity 100. To produce the 101st unit, you will need to invest in new machines, new labor & increased overheads. After a point of time, the cost shoots up. Hence the increase in marginal cost.

Essentially, the above property of marginal cost suggests that there is a limit to how big a company can grow and sets a limit on the supply. This is what experts call "scalability".

Now, let's come to natural monopolies. There exist firms for which marginal costs are always decreasing, i.e. perpetual economies of scale.

What does this mean? It means that such firms have the fundamental attribute to grow huge in their chosen markets since they have no limit on how much to supply. That's why they are called "natural monopolies" since they are fundamentally built to dominate markets. Some conventional examples of these are railways, pipelines etc.

For any competitor which arises, it would make sense to merge to enjoy the additional economies of scale.

I contend that platform businesses are natural monopolies by design. In fact, most tech companies today are natural monopolies. They incur lower additional cost to serve newer customers.

Network effects

Network effects are relatively well known. It is when the value of the good increases as more people are using it.

However, I would like to introduce the following two types of network effects:

Cross Side & Same Side network effects: Cross side network effects are when the value of the good or service increases because of more number of users on the other side. E.g. Uber provides more value to customers when there are more drivers because of shorter waiting times & more benefits to drivers when there are more customers (lower idle times). The same side effects are when the value addition is on the same side. E.g. Users of Facebook have same-side network effects. The same side network effects are more potent because there is no intermediate equilibrium reached until network effects vanish.

Local & Global network effects: Local network effects are when the network effects are limited to a particular customer segment, usually geography. E.g. Uber has strong local network effects only within cities. Global network effects are when the network effects are for many customer segments. E.g. AirBNB has primarily global network effects. The value of the service increases for me when there are rooms available for me in another country. Global network effects are more potent because they apply over a larger pool of customers.

Difficult to differentiate

Let me define differentiation first. Differentiation is when you create a valuable perception of your product or service in the minds of the customer. Differentiation is purely from the customer's point of view and differences in internal operations of companies don't constitute differentiation. That said, let's move ahead.

Imagine yourself to be the product manager of Ola. You wake up in the morning, and you get ready to go to the office. You have your breakfast, and you check the Ola app. There's high waiting time. You check Uber, and you realize they have launched a new feature!

You grab an Uber, reach the office, and call an emergency team meeting and compare your metrics. Their latest update seems to have improved their metrics significantly! How did you not think of this feature?!

You sit down with your developers and try to reverse engineer it. The adrenaline rush that you felt when you saw the feature is now wearing off. Your brain has started working again. You steadily begin figuring out what the Uber team did. By the end of the day, the team has figured out how to implement the same feature for Ola.

You schedule the required deliverables and take a long but satisfying ride home. The feature can be implemented by Ola before the end of next week.

In technology products, it's challenging to differentiate based on products or features. Any new features that a company launches can be reverse-engineered and implemented in a short time by the competitor.

To all the product managers, this is how I imagine things like these happen and am only trying to make a point. Of course, since I am no product manager myself, I have no idea whether it's realistic or not. Please forgive me for hyperbole. :)

Network effects & Natural Monopolies: A powerful chemistry

When we look at the fact that platforms combine both these above properties, we come to understand why VCs love platform businesses. Both properties complement each other really well.

Network effects grant economies of scale.

Once the user base reaches a critical mass, by virtue of network effects, platform businesses can rapidly increase the number of users they can serve. Simultaneously they reduce their customer acquisition costs resulting in a significant decrease in marginal cost.

Economies of scale improve network effects.

The economies of scale of natural monopolies allow firms to price low and onboard new users faster. This facilitates the creation of the said critical mass, which is followed by lower costs.

What we have got hence is an entity that grows faster and becomes increasingly profitable as it keeps getting bigger. This entity is poised to beat any competitor that tries to enter its market.

The implications of this are very significant. Considering that the above three assumptions hold, we may draw the following implications about platforms:

Implication 1: The efficient equilibrium of a platform is a monopoly

Even though there may be multiple competitors in the market, the larger company has a cost advantage because of which it can undercut prices and capture a significant chunk of the market. Usually, when other markets face this problem, companies try to differentiate. But in this case, companies can't differentiate. The larger company's rate of growth will also be faster due to the network effects afforded by it. It is also more efficient for the competing firms to merge so that their costs are much lower. Even when they don't merge, the bigger firm can outprice and outgrow the smaller firm.

Implication 2: First Mover Advantage holds

Let me elaborate. The first firm to reach the critical mass of users where strong network effects kick in will be the winner. This logically follows from Implication 1 since the first company to get strong network effects will be bigger than other competitors and will have an advantage. This is conditional on whether the first mover reaches the critical mass early.

Implication 3: Niche firms if they exist, are unattractive compared to the bigger firm

Because Niche markets are small and the products are difficult to differentiate, even with network effects, a firm cannot reach the scale at which begins to become economical. E.g. think of a boat cab service company. Can it ever be as attractive as Uber? No. Can Uber just do it by itself? Yes. It just ate up that market.

"All these theories are well and good. But do they ever work in real life?"

Well, let's do precisely that and apply the above to these cases. But before we go on, I'd urge the readers to think of a platform business they like, think of the above three assumptions, and see whether they match or not. If they match, are the implications correct? If they don't match, how do the implications change? Let’s explore.

Case 1: Google & the Search market

While Google has become so much more in recent years, I'd like to talk primarily about Google Search.

Google is the quintessential example of a platform. Let's look at its characteristics.

Difficult to differentiate? Yes. While Google did patent its PageRank algorithm, there was a lot of academic work going on around ranking web pages which posed a credible threat in terms of competition. Until 2002, Yahoo had been using Google for search but built it's own very similar search engine by acquiring companies.

Presence of network effects? Yes. Same side network effects exist. My Google search results keep improving because a million other people are searching on Google. Cross side effects also exist, i.e. my value for google keeps increasing as it keeps on indexing more websites. Cross side network effects exist for website owners also, which is why everyone wants to optimize their SEO ranking.

Another property of Google Search is that it has Global network effects because the value of the platform increases regardless of who the user is or where he/she is located.

Economies of scale? Yes. Google File System is highly scalable because of wise decisions the company took in the initial years.

Now let's check the implications.

Is Google a monopoly in the search market? A resounding yes.

Was Google the first mover? Interestingly, no. Yahoo existed for a full two years before Google came. However, Google was the only platform that had economies of scale because of its file system. At the same time, Yahoo, with its application infrastructure, was "unable to keep up with increasing demand due to complex & inefficient infrastructure and rising vendor costs"(Source: Techcrunch). Google was built as a natural monopoly; Yahoo wasn't. Naturally, it was Google which triumphed even though Yahoo had the first-mover advantage.

Lastly, do niche markets exist, and if so, are they as attractive? Yes, they do but they aren’t nearly as successful as Google. An intriguing niche, in this case, is DuckDuckGo, which has created a space for itself as a privacy-friendly search engine. DuckDuckGo has successfully differentiated itself and has got a loyal segment of customers because of which it is able to operate in the said niche.

Case 2: Uber & the ride-hailing market

While the market is still immature, there are specific patterns we can see happen in this case.

Is it challenging to differentiate? As illustrated by my example above, yes.

Is it a natural monopoly? Yes. Being an asset-light model and owning no cars means that Uber enjoys infinite economies of scale.

Does it have network effects? This is where things get interesting in the case of Uber. Uber only has cross-side network effects & primarily local network effects in cities. Cross-side network effects mean that Uber will have to keep incentivizing one of its sides to grow, which means that even though economies of scale exist, the pace of cost reduction is slow, and hence the growth is also relatively muted. Local network effects in cities mean that Uber has to grow individually in cities. Simply put, having an extra cab in Mumbai doesn't get me a customer in Delhi. Hence, I need to have cabs in both Mumbai & Delhi to get customers there.

This means that for something like Uber, we have to make some adjustments to the implications.

The ride-hailing market's efficient equilibrium is city-wide monopolies, and the first-mover advantage is limited to cities. We do see these patterns emerging. In the U.S. market, we see Uber & Lyft performing well in certain regions. Uber has also made tactical exits from the Chinese & the South-East Asian markets where it has realized it cannot compete because there were first movers there in many cities.

Even in India, Ola beat Uber by establishing a presence in Tier-II & Tier-III markets before Uber.

Given all the above information, what makes sense for Uber? In my opinion, Uber must make critical mergers & acquisitions to become profitable. In markets where it has exited, it should look for investment opportunities in the ride-share companies there. Uber should consider merging/acquiring & investing with Lyft, Didi & other competitors.

Case 3: Amazon & the e-commerce market

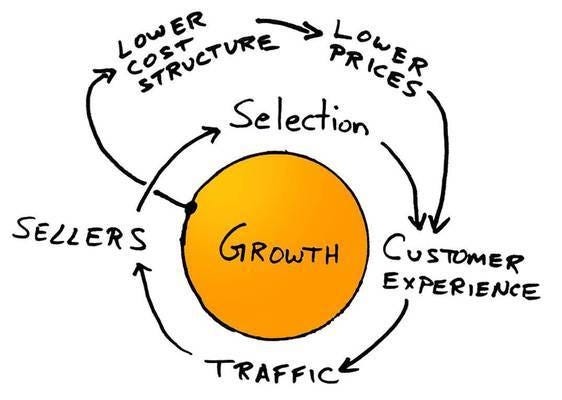

Amazon is a firm that understands the dynamics between economies of scale & network effects better than anyone else. If we look at the Amazon business model flywheel, it encompasses everything we talked about.

Is it difficult to differentiate in the e-commerce market? Yes. Features can be copied very easily across platforms.

Do network effects exist in the case of Amazon? Yes. National network effects do exist in the case of Amazon.

Does Amazon have perpetual economies of scale? Let's explore this. Amazon is not exactly an asset-light model. Warehouses, delivery agents, trucks, etc. have limits. To serve an extra customer who lives in a remote village, the marginal cost will be higher. That said, the economies of scale exist for much longer than traditional brick & mortar models. It will cost lesser for a business or a customer to send the good via Amazon than a courier. This tells us why other asset-light e-commerce platforms like eBay weren’t able to threaten Amazon. While it doesn't have perpetual economies of scale, the range of economies of scale is still higher than traditional models.

However, since a limit does exist the e-commerce market does not necessarily need to be a monopoly. However, strong network effects still do create a huge entry barrier, so first-mover advantage does exist in a more traditional sense. This is good news for Flipkart & Amazon India!

However, this also means that the e-commerce business isn't hugely profitable compared to other platform businesses. Amazon's retail business's profit margins in 2018 were 3.8% while Facebook's margins are >40%. Amazon is well aware of this and has hence branched into alternate industries, i.e. cloud services & advertising.

Lastly, one should also note how Amazon aggressively acquired niche e-commerce platforms which comes naturally because of high economies of scale & low differentiation.

Conclusion

The above learnings and insights have applications for a diverse group of people. While reading the above article, a startup owner might think, "Okay, I need to plan for scalability of my platform". In contrast, a regulator might think, "Maybe breaking up big-tech is not the most efficient economic outcome." But those are thoughts for another article. Either way, I hope you have some personal takeaways from this article.

If you liked it and feel that it added value to your day, please consider sharing it! Also, we would love to hear your thoughts & comments down below.

We’ve covered quite a few topics so far. Why don’t you take a look at them here? We’re sure you’d like them.

We’re constantly listening to you for suggestions and feedback to improve. We’ve also added a section for you to recommend a good podcast/article/post/Tweet(s)/video to the community. If you want us to acknowledge you, drop in your name/link to your LinkedIn/Twitter profile in the space as well.

So, it’d be great if you let us know how you like our newsletter so far.

What we’re reading/listening to/watching this week -

After pulling the plug off Vine, Twitter wants to buy TikTok